Our daughter Mckenna is 18 years old. She is our first born, and she was placed in our arms when we were only 18 and 20. She is intellectually disabled, on the autistic spectrum, has major depressive disorder, OCD, and oppositional defiant disorder. She is also a burn survivor; at age 8 her shirt caught fire in our kitchen and she sustained third degree burns on 20% of her tiny body. She was hospitalized for three months. She almost died. Kenna has never been quite the same since that tragedy, and the last ten years have been incredibly difficult parenting her as she pulled further and further away.

To give you more of an idea about what I’m talking about, here is an excerpt from a post I wrote in August 2010, titled ‘More on the Subject of Truth’.

“And something I didn’t go into on that last post. I didn’t get specific enough about what I was dealing with. My daughter Mckenna has an undiagnosed neurological disorder that causes her to have major agitation over simple household noise, major issues transitioning from one thing to another, (even something as simple as getting out of the car), and obsessive compulsive tendencies. She is unpredictable in when she will melt down, but melt down she does. And often. In a meltdown she screams, she will try to take off her clothes, she will lay down on the ground. Often in public, right where people have to walk around her. She will stop everything she is doing, like a stubborn horse you can’t get to move an inch. You pull and yank on the reigns and plead and beg and they just dig in their heels. So does she. She will yell curse words. This started in middle school – she doesn’t know when not to curse like the rest of the kids. (Around teachers and parents.) She has zero social or safety awareness. She has no idea people like their space, and will walk up to someone and touch them inappropriately as she says ‘hello’, or ‘hi, dude!’ She has no idea that she could get hit by a car in a parking lot. In 2006 she left our house unannounced twice, and took off on foot. One time before 6am, when everyone else was asleep, the other time when the kids were playing outside and I was upstairs folding laundry and didn’t realize she had left. Both times we were frantic to find her, and were lucky we did. After her second attempt, we purchased a $300 personal GPS system that she had to wear for months. If she got more than 10 feet away from the base, her bracelet would ring an alarm. A lot of the time, her safety is out of my control, and I live in fear of what may happen to her next. She is intellectually disabled with some autistic like symptoms. We don’t know why and we probably never will. It isn’t for a lack of trying. She is fourteen years old and we have taken her to the doctor to try and figure her out countless times.”

This is another excerpt from a different post in August 2010:

“The confusing thing with Mckenna is that there are moments of astonishing peace and joy for her, … Those are the moments that hold me over through the bad ones and make me sane, but they also tease me into believing that she can have MORE moments like that, if only I try harder. If only I give more. If only I fix her.

And I can’t. She is not “fix-able”. Whatever good moments she has, are most likely nothing to do with me. Just like whatever bad moments she has, are most likely nothing to do with me. They just are. They just exist for whatever reason the synapses in her brain allow them to exist in that moment. She is unexplainable and impossible to solve. Mckenna is not free. She is locked up and hidden from me most of her days and most of her life. Those moments that I cling to are few and far between, and yet I kill myself everyday to try and get more of them.”

Those words were written almost exactly four years ago, at a point in time when I was staring down the tip of a very large iceberg, beginning to see that something needed to change. Up to that point, we had tried everything we could think of to help her, but she wasn’t making progress, and she wanted nothing to do with our family as a whole. In fact, her behavior was getting worse by the day and she was sinking into a hermit like existence, even refusing to go to school. My overwhelming desire to keep my family together, which I had decided was “THE RIGHT WAY” , was no longer working. I was finally able to see that we needed to respect her need for independence, and that we couldn’t continue in the same way we had for years.

And we finally got some help.

First, we told our Regional Center caseworker that we needed help. We called emergency meetings and made necessary changes to Mckenna’s yearly goals. We were awarded more respite hours, behavioral therapy four times a week, and given an appointment for a major psychological evaluation. At this point, she was just about to enter high school. “Miss Pam” was her new teacher, and she was an ANGEL IN DISGUISE. She worked side by side with us on Mckenna’s behavior plan to make sure things were consistent at school and home. She constantly went above and beyond for our family.

Just one example happened right away as we struggled to get Mckenna to ride the bus. Pam knew this was an integral part of Mckenna’s impending adulthood and vital to her independence, so she needed to master it. Pam talked to us and we decided that she would get two choices: “bus” or “walk home”, about three miles. Well, the day inevitably came when Mckenna chose “walk home” and Miss Pam walked with her all the way to our house. Mckenna never chose “walk home” again. It takes a huge level of commitment and competence to do something like that as a teacher, and I will never forget it.

Something else we needed to do was find people that could be with Mckenna while we got a break. We had never, ever left her with anyone other than family, every once in awhile. Pam pushed me gently into this, knowing more than I did how much we needed it. She connected us with people in the special education community who were looking to work, and we hired several of them to help us at home on a weekly basis.

Oh yes, and that psych evaluation. It was a three hour appointment that took place at UCI. A handful of specialists from the same psych department took turns observing Mckenna, and interviewing Jeff and I. That was when we got the diagnosis’ that I listed in my first paragraph, along with a prescription for an anti-depressant for Mckenna. It was given in the hope that it would help her come out of her seclusion, reduce depression and anxiety, and help her sleep. None of the disorders we use to describe our daughter are the big answer – we still have no idea why she is the way she is, why she was born this way – and we are in good company, part of a large and ever growing percentage of families that have children with some type of undiagnosed neurological disorder.

Over the next few years, we worked closely with behavior therapists, school personnel, and her psychologists to get her to a higher functioning place. She never went back to how she was before the burn. She didn’t decide to start eating with us again, or go on outings with us, or vacations. She still had meltdowns, however they were less frequent and less severe. There became a new normal. She thrived on her outings with caregivers and in her social peer group that met once a week. We moved our regular house cleaning day to Saturday, so that the woman who takes care of our home could also keep an eye on Mckenna. That gave the rest of us one day a week to leave the house together. One day a week to have freedom and connect with our other kids.

Letting go of the idea that we must all stay together gave us a new kind of life.

Mckenna began to look forward and depend on her quiet Saturdays spent at home with Olivia, and we loved our weekly family day. It became precious to all of us. We saw that if we stayed home on a Saturday, or if she wasn’t getting to go out independently during the week, her mood and behavior became worse. So we made it a priority.

What became difficult at this point was the stark contrast. Suddenly, we were juggling two separate family units. One with Mckenna, and one without. And it was hard to navigate for awhile. When you are living your life day in and day out dealing with a very difficult child, you don’t realize how hard it is and how exhausted you are until you take a step away. Once I stepped away into the “normal” world with my other three children, we all relaxed, and I could see how toxic Mckenna’s personality and behavior could be to us. And that…sucked. That really fucking sucked. We would go out with the other three kids and have a lovely, spontaneous, carefree day, and then come home to a violent meltdown or a very dark mood. And that would hurt so much. So, so much. It was almost to much to take at times, and there were many parental meltdowns of our own. It brought on so much pain, to be faced with that contrast. Not only was I suddenly very jealous of people who lived their lives with typical children, it saddened me greatly that she couldn’t assimilate into our world. I would just cry and wonder, “Why did this happen to her? Why can’t she be happy? Why is she so angry? Will we ever be able to make it through this?”

It was in her sophomore year of high school that she started talking about turning 18. She would say to me, “When I turn eighTEEN I am going to go to college. When I turn eighTEEN I am going to move in with my friends.” The first time I heard that come out of her mouth you can imagine my shock. I was like, “Oh, realllllllllllllly?!” I had been talking for years in therapy about the possibility of Mckenna not living with us at some point. I never imagined it would happen. I didn’t even know that she would understand the concept. But oh, she did. And she didn’t stop talking about it from the time she turned seventeen.

Every single day, multiple times a day, we were asked, “When do I graduate from high school?”

“June 2015.”

“When do I go to college?” (She refers to the Adult Transition Program which runs from ages 18-22 as “college”.)

“July 2015.”

“When do I move in with my friends?”

“When you graduate.” (And then the wrinkling of the brow as she realized she didn’t like our answer.)

And over and over, and again and again. We were suddenly faced with the choice we never wanted to make. But more than anything else that we know about Mckenna, we know that she knows what she wants. And if this was what she wanted, we would figure out the best way to get it for her.

Again, I went to Regional Center and told them the newest information. We learned about our options for housing and support after she turned 18. We learned that we needed to be granted conservatorship over our daughter. That meant we would have to hire a lawyer and go to probate court to take certain rights away from her because she was unable to make certain decisions. (Medical, financial, etc) After hearing about many housing options, we decided the best thing to start with would be a group home. She would be in a familiar home type environment, but have more independence. Since she worked well in a group setting at school, and needed a lot of assistance and care, this was our best bet. We decided to look into our options and wait until she was out of high school to make any changes.

Except, Mckenna had other plans.

Once she turned eighteen in the spring of her junior year of high school, she began getting more and more annoyed that she wasn’t moving out or going to college. She still had over a year of high school left, and it was really bothering her. Her behavior ramped up, she was later and later to school every day, and she would get angry when we couldn’t give her exact dates for when she would “move in with her friends.” She just started going downhill, and we were very concerned. Jeff and I honestly didn’t know how we were going to make it through another year of school, when she was so unhappy.

I don’t remember how we came up with the new plan, but it seemed like one day we thought of the idea and the next day it was all put into action. Everything happened so, so fast. It was just like, LIGHTBULB, why are we making her stay in high school when all she wants is to go to college? We asked our district if we could change her status to a senior since she was 18, meaning she would graduate in 2014 instead of 2015. They said yes. In March of 2014, we held an IEP. (For those not versed in the special education system, an IEP is an Individual Education Plan, held once a year.) We began the process of moving her to Adult Transition, which is the last step on the special education rung. Our Regional Center caseworker started looking more seriously into group home locations for us to visit and check out. We desperately wanted her to remain in the same school district, as close to home as possible, but we also knew that if we found a home that was an hour away that Mckenna loved, we would do that, too.

We told Mckenna that she was a senior and that she would graduate and go to college **IN 2014**. I wish you could have seen her face. It was relief and joy and excitement and pride all rolled into one.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

Mckenna’s story continues soon.

To read more about her past, you can click the “Mckenna Mooneyes” tag beneath this post or click this link.

You may also be interested in checking out the #mckennamooneyes hashtag I’ve created on Instagram.

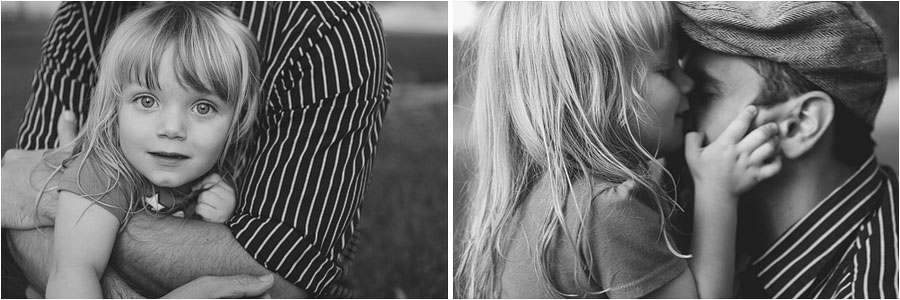

**The photos used in this post were taken on her 18th birthday and on a Disneyland trip to celebrate her, with film and a Nikon One Touch.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————-